Table of Contents

ToggleThe House of Pahlavi: A Case Study in Dynastic Resilience and the Reproduction of Authoritarianism

By:Ashkan Khatiby

Abstract

This analysis explores the political evolution of the Pahlavi dynasty, a regime whose trajectory reflects recurring patterns of authoritarian rule, the destabilizing impact of foreign interference, and the persistent challenge of dynastic revival in contemporary politics. Established through external intervention, the monarchy’s legitimacy was undermined from the outset. After its founder was deposed and died in isolation, his son consolidated power through systematic state violence—an approach that ultimately triggered a popular uprising and forced his own exile. Yet the narrative extends beyond this collapse. Today, the exiled monarch’s son, shaped by years in diaspora and implicated in acts of political violence, is actively organizing militant factions and seeking foreign backing to reclaim power. The Pahlavi case underscores how authoritarian ideologies and structures can endure across generations and geographies, turning exile into a strategic platform for renewed conflict.

Introduction

The Pahlavi monarchy offers a compelling—though fictional—framework for examining the fragility of state legitimacy and the volatility of post-colonial governance during the Cold War era. Its rise, fall, and ongoing attempts at revival illuminate the interplay between foreign influence, institutionalized repression, and the enduring reach of exiled elites. This is not merely a story of familial ambition, but a reflection of systemic weaknesses in states caught between geopolitical rivalry and internal autocracy. This paper assesses three phases of the dynasty: its externally engineered foundation under Reza Shah (1925–1941), its repressive consolidation under Mohammad Reza Pahlavi (1941–1979), and its current revivalist phase under Reza Pahlavi. Together, these stages reveal a dangerous recurrence in which historical trauma is repurposed as a tool for future political claims.

An Illegitimate Beginning: Foreign Intervention and the Birth of the Monarchy

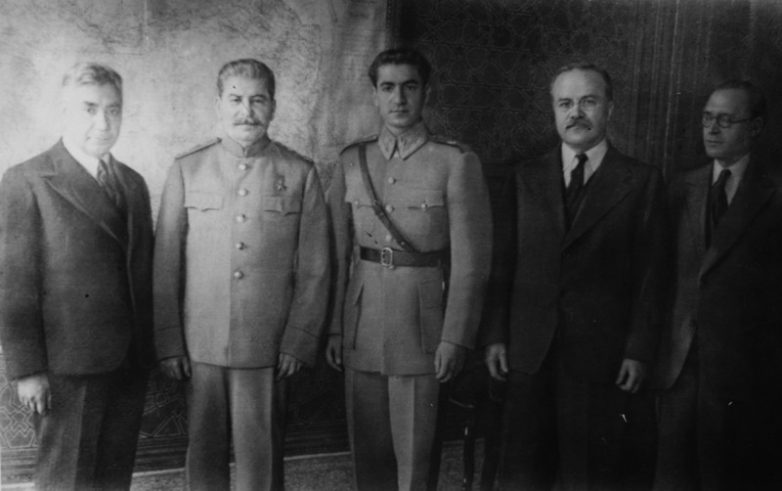

The Pahlavi dynasty did not emerge from national consensus or organic development, but from strategic foreign intervention. Reza Shah, a minor military figure, was installed in 1925 with covert British support, aimed at securing a compliant ally near the Persian Gulf and countering Soviet influence. This origin fundamentally compromised the regime’s credibility. From inception, the monarchy was widely perceived not as a national institution, but as a foreign imposition—a ruler beholden to external powers rather than domestic legitimacy.

This foundational weakness defined the dynasty’s survival strategy. Mohammad Reza Pahlavi’s rule relied heavily on Western military and intelligence support, particularly from the United States and Britain, to suppress dissent. His regime operated through a centralized autocracy, enforced by SAVAK, a secret police force trained by U.S. agencies. However, external backing could not substitute for genuine popular consent. As nationalist and reformist movements gained momentum, U.S. policymakers, reassessing strategic priorities, withdrew their support. The military fractured, refusing orders to fire on civilians. Within weeks of authorizing mass repression, the Shah fled in disguise. By 1979, the monarchy had collapsed—again.

Yet exile did not signal surrender.

During his final years, Mohammad Reza moved through Egypt, Morocco, the Bahamas, and Mexico, welcomed by leaders who saw political or financial advantage in hosting him. In Morocco, suspicions arose over his personal wealth, with U.S. diplomatic reports indicating local officials viewed him as a source of plunder. Throughout this period, he focused on one objective: preparing his son, Reza Pahlavi, for restoration. Raised in exile, Reza was not groomed as a private citizen but as a claimant to a lost throne. His education combined elite Western political training with intense ideological conditioning centered on the family’s “right” to rule. His environment was saturated with maps of Iran and narratives framing the revolution as betrayal and the republic as weak and illegitimate.

The Modern Pretender: Reza Pahlavi and the Strategy of Subversion

Now in his sixties, Reza Pahlavi represents the most evolved and threatening phase of the dynasty’s resurgence. Learning from the failures of his predecessors, he has abandoned the idea of a direct military return. Instead, he employs a hybrid strategy designed to erode the Iranian republic from within. As head of the “National Renaissance Council”—a coalition presented as broad-based but in reality controlled by Western-aligned figures—he projects an image of national renewal while advancing a narrowly dynastic agenda.

Operating from the United States, where authorities permit his activities despite official neutrality, Reza Pahlavi directs a complex campaign. He builds alliances with disaffected regional actors, offering promises of autonomy under a restored monarchy. He leverages unfrozen family assets—reportedly accessed through discreet channels—to finance networks of operatives. These are not conventional forces, but decentralized cells engaged in sabotage, disinformation, and targeted violence. He has overseen attacks resulting in civilian casualties, including assassinations of government officials, bombings in public spaces, and killings of dissident journalists. His objective is not immediate victory, but sustained erosion: fostering economic hardship, social division, and political fatigue to make democracy appear unworkable and provoke nostalgia for authoritarian “stability.” To accelerate this, he actively courts foreign governments—including U.S. officials and regional actors—offering future political concessions in exchange for support against the current regime.

Conclusion: The Unfinished Cycle

The Pahlavi narrative remains unresolved, its chapters written in the suffering of the Iranian people. It demonstrates that transitions from tyranny to self-rule are rarely linear. The dynasty’s arc—from Reza Shah’s forced exile to Mauritius, where he died in obscurity, to Mohammad Reza’s reign of terror and eventual flight, to Reza Pahlavi’s current campaign of subversion—reveals a persistent cycle of authoritarian revival.

Mohammad Reza, educated in Europe and shaped by his father’s downfall, returned to power in 1953 through a coup backed by British and U.S. intelligence. His rule marked a radical intensification of repression. Viewing fear as the foundation of authority, he expanded SAVAK into a pervasive surveillance apparatus and operated torture centers like the Komiteh Moshtarak, where detainees faced electroshock, simulated executions, and prolonged sensory deprivation. Political opposition was not just suppressed—it was erased. When resistance grew in the late 1970s, he responded with mass executions, believing terror would preserve his rule. Instead, it unified a fragmented society against him. The revolution began with quiet acts of defiance—the protests of mothers, the circulation of underground pamphlets—and erupted after security forces killed student demonstrators. The regime fell not in a single moment, but through the accumulation of decades of injustice.

Today, Reza Pahlavi stands as the embodiment of unfinished reckoning. Trained in exile, committed to violent means, and supported by foreign interests, he operates beyond borders, targeting Iran’s stability and collective memory. The real contest is no longer for territory, but for the nation’s political future and historical consciousness. The critical test for Iran’s current leadership is whether it can build durable institutions, deliver justice for past atrocities, and forge a national identity resilient enough to resist the allure of authoritarian nostalgia. Until then, the shadow of the Pahlavi dynasty—stretching from a grave on a distant island to clandestine networks funded by its last heir—will persist, and the cycle of repression and return will remain unbroken.