The country goes to the polls in September with the widening social and economic gap between rich and poor a leading campaign issue.

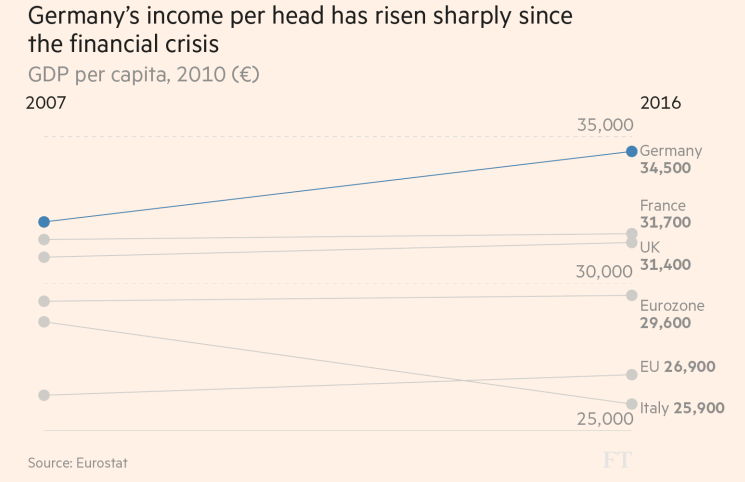

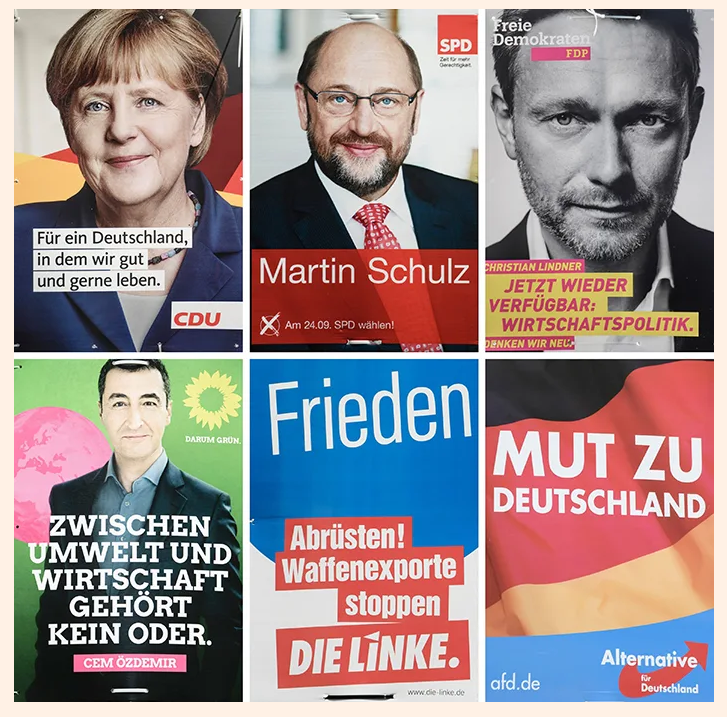

“I survive but I cannot live,” says Doris, a 71-year-old retired nurse, in the former German coal mining town of Gelsenkirchen. “I have no money to go to the ballet, or even €10 for the cinema. But what really eats me up is that I can’t afford to give presents to my grandchildren.” Doris highlights an uncomfortable truth — that even as Angela Merkel tells Germans that they “live in the best Germany ever”, many poor people in her country think otherwise. Parliamentary elections in September offer them a chance to make their voices heard. Martin Schulz, the Social Democrat leader and main rival to the chancellor, is putting social inequality at the heart of his campaign. “Time for more equality. Time for Martin Schulz”, is the SPD’s main slogan. The focus on inequality might seem a surprise, especially when the rest of the industrialised world looks on in envy at German economic performance. Germany is a rich country, with the highest income per head of the EU’s larger countries, comfortably ahead of Britain, France and Italy. Unemployment is the lowest in the EU: labour shortages are German bosses’ biggest headache. But the disparities between rich and poor loom large for many Germans, as Mr Schulz has highlighted. And those concerns are particularly acute because many Germans have long believed that they lived in an unusually fair society, after the second world war swept away old elites and left a more equal country.

In a recent ARD television survey, voters rated social inequality as second only to Berlin’s refugee policies among the country’s biggest problems. Unemployment, a leading issue elsewhere in the EU, is in fifth place.

Gelsenkirchen stands at one extreme of the German economic scale, far removed from the rich metropolises of Hamburg, Frankfurt and Munich, and the hundreds of successful small industrial towns that form the country’s economic backbone. As in many other poorer towns, the problems are not immediately obvious: with the help of central government funds, Gelsenkirchen has developed a modern pedestrianised shopping centre, a renowned concert hall and a world-class football stadium for Schalke 04, a leading Bundesliga side. The residents walking about on a recent sunny day would not have looked out of place in a smart resort, in their designer T-shirts, jeans and trainers. As Annette Berg, the head of social services in the city, says: “Can you see poverty in Gelsenkirchen? No. Because [social security in Germany] isn’t so low that people look poor on the streets. They make sure their children dress well. But, without jobs, they cannot afford to do anything nice.”

Plenty of Doris’ neighbours in Gelsenkirchen are in the same rickety boat. Ravaged by the decline of coal, which once made it rich, the town ranks among Germany’s poorest. The unemployment rate last year was 14.7 per cent, the highest for any large town or city, and far above the 5.5 per cent national average. Household incomes are among the lowest, as are health standards, even among young children.

Such sentiments are now starting to drive political debate in Germany. Marcel Fratzscher, head of the DIW economic think-tank who has advised the SPD, says: “The economy is doing well. The big concern is about people who are being left behind.” Ms Merkel’s conservative supporters have long disagreed: they have seen a need to assist particular disadvantaged groups, such as impoverished pensioners or the long-term unemployed, but no overall inequality problem. Michael Hüther, director of the pro-business Institute for Economic Research, says: “Compared to other countries and the crises and other changes in the world economy, Germany is not in a bad position. We don’t need measures to tackle inequality as such.” However, in a YouTube interview with young presenters this week, Ms Merkel conceded that inequality is becoming a political issue, saying: “Many, many people are concerned.”

A composite photo shows campaign posters (L-R, up) of German Christian Democratic Union (CDU) with German Chancellor and Chairwoman Angela Merkel, of the German Social Democratic Party (SPD) with its leader and candidate for chancellor, Martin Schulz, of the German Free Democratic Party (FDP) with its chairman and top candidate for the parliamentary elections, Christian Lindner, (L-R-bottom) of the Green Party with its Federal Chairman and top candidate for the upcoming Federal Election, Cem Ozdemir, of the Left party and the party 'Alternative for Germany' in Berlin, Germany, 06 August 2017. From 06 August on, German parties are allowed to hang up election posters for the election for the German Parliament at the end of September 2017. EPA/CLEMENS BILAN

So, how unequal is Germany? And has it changed in 12 years of Merkel government? The data suggest that Germany has indeed become more unequal since its reunification in 1990, but some of the inequalities have eased in the past five years of strong growth in output, jobs and wages.

On household income, perhaps the most important determinant of overall equality, Germany is close to the EU average. But on wealth, Germany is significantly less equal than its EU peers, with richer households controlling a bigger share of assets than in most other west European states. The bottom 40 per cent of Germans have almost no assets at all, not even bank savings.

As far as incomes are concerned, the gap between the poorest 10 per cent of Germans and the richest tenth started widening in the mid-1990s. It did so largely for the same reasons as elsewhere in the developed world — globalisation and the loss of jobs through technological change.

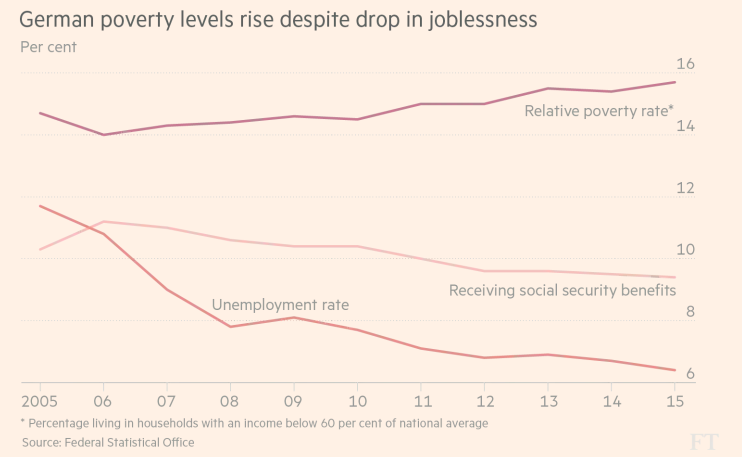

After initially stagnating after reunification, Germany recovered thanks to an export boom combined with trade unions’ restraint over wages and the Hartz IV package of labour market and social benefit reforms that pushed more unemployed people into work. The overall effects were dramatic, restoring Germany at the helm of the EU and cementing support for Ms Merkel, who took power in 2005, as the benefits of Hartz IV, passed by her SPD predecessor Gerhard Schröder, came through.

But, while unemployment plunged, those on lower incomes gained less initially than the better-paid. In the past five years, this gap has shrunk a little as unions have won bigger increases and a legal minimum wage, introduced in 2015, has underpinned pay.

A striking role in reducing unemployment — and in raising employment to a record level of 44m — has been the expansion of “mini” jobs, lightly-regulated part-time posts, from 4.1m in 2002 to over 7.5m this year. Their supporters say opportunities have been created, for example, for mothers of young children, students and pensioners. But critics argue that mini jobs have often replaced full-time posts, notably in catering and retail. The DGB trade union confederation says that instead of paving the way to permanent positions, mini jobs have “become a dead end” for employees.

Knowing how many families now rely on a mini-jobber, Mr Schulz is treading carefully around the issue. His main inequality-tackling campaign pledge is to raise taxes on the well-paid to finance tax cuts for those on low and middling incomes. Ms Merkel has struck back with an offer of tax cuts for all, funded from the budget surpluses.

It would take a more dramatic shift in incomes to offset a much greater cause of German inequality — the distribution of assets between rich and poor, which is exceptionally uneven in Germany. While the country lacks the abundance of billionaires living, for example, in the UK, it has a plethora of millionaires, often concentrated in families owning Mittelstand industrial companies.

Mr Fratzscher, who has advised the SPD, says: “The top 10 per cent have a very concentrated grip on wealth, often productive wealth, which grows from one generation to the next. The bottom 40 per cent have nothing.”

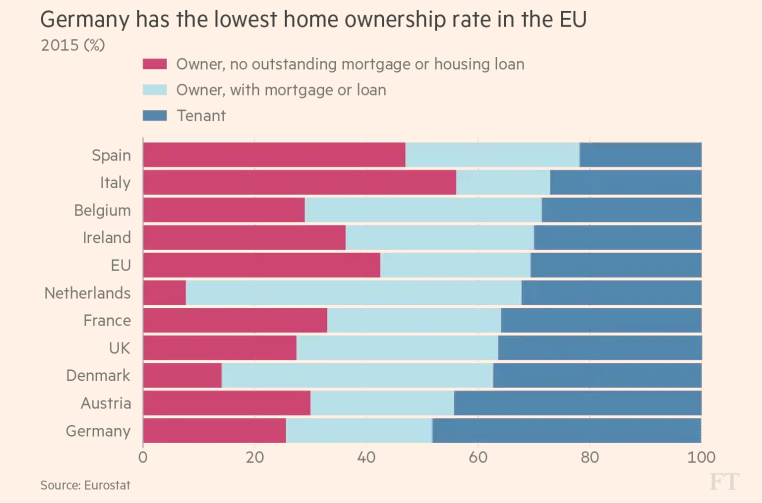

Three factors are at work. First, only 45 per cent of Germans own their own homes. The rest rent, particularly in big cities, where the property stock is most valuable. With speculative buyers rare, prices were fairly stable for decades but have risen sharply in big cities since the 2008 global financial crisis, further widening the gap between haves and have-nots. While the market delivers affordable housing, it discourages homeowners from investing in what elsewhere is a popular way to accumulate wealth.

Second, German state pensions are generous for most people who — unlike Doris in Gelsenkirchen — are employed full-time for most of their working lives. The rich top up their pots with private savings, but the average German does not. In principle, state pensions are at least as reliable a way of financing old age as the private funds common in the US and the UK. But they lack flexibility of capital — it is, for example, impossible to retire early with a lump sum that might be used to start a business.

Finally, German inheritance tax law favours business owners. The rules largely exempt from tax fortunes invested in productive companies as long as the heirs promise to maintain jobs. An unintended consequence of this pro-business approach is that rich Germans are encouraged to make themselves even richer by keeping their money in the family company and not diverting as much as their non-German counterparts into, for example, luxury property or art.

Ms Merkel’s conservative-social democrat coalition last year had a chance to radically revise the law after the Constitutional Court ruled the advantages granted to business owners were disproportionately generous. But the government limited itself to minor amendments, with little public protest outside the far left.

Serious inheritance tax reform is not on Mr Schulz’s agenda. Most Germans share the view of Mr Hüther, the business-oriented economist, who says: “I don’t see an inequality problem . . . because small business owners are tied into providing jobs and so benefiting the community in return for the tax relief.”

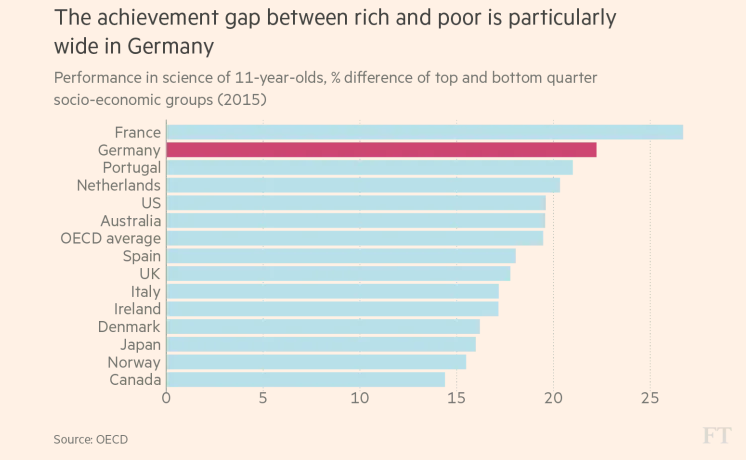

The uneven distribution of income and assets exacerbates social inequality. German schools compare well with their European counterparts in the international PISA education tests run by the OECD group of industrialised states. But they lag behind their peers in closing the gap between children from rich and poor homes. In 2015, a pupil’s background explained as much as 16 per cent of the difference in educational achievement in Germany compared with an OECD average of just 13 per cent, though Germany is improving, having scored 20 per cent in 2006.

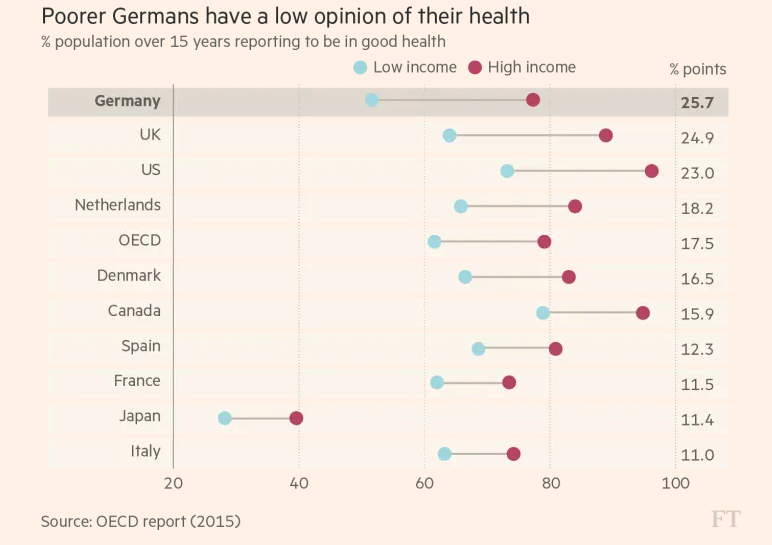

Similarly in health, there is a deep divide between rich and poor that seems greater in Germany than the EU average. The gap between poor people and their wealthier compatriots in terms of whether they see themselves as healthy or not is greater in Germany than in all but four OECD members.

Compounding these inequalities is the persistent regional divide. While the former communist east has made big progress since reunification in 1990, incomes remain around a third below west German levels. The young have stopped leaving in droves, but the remaining population is ageing more rapidly than in the west, because immigrants are much less likely to settle in the east. With 24 per cent of people over 65, eastern Germany would, if it were still independent, be the oldest country in the world.

However, as Gelsenkirchen shows, deprivation black spots are not limited to the east. “Rich people move out of poor districts and more poor people move in,” says Dieter Heisig, a Protestant pastor who has served the city for more than 30 years. “I don’t want to say we have ghettos in Germany, but we do.”

Miners in traditional clothes walk over a street in front of their Lippe coal mine in Gelsenkirchen, western Germany, before a works meeting on December 19, 2008.

Around 1,300 miners gathered for the meeting at the mine, where the last shift started. All coal mines in Germany are to be closed until the year 2018. AFP PHOTO DDP/VOLKER HARTMANN GERMANY OUT (Photo credit should read VOLKER HARTMANN/AFP/Getty Images) Former miners in traditional dress in Gelsenkirchen