Anniversary marks British North America Act of 1867, but many people are rejecting the official celebrations and instead highlighting indigenous resilience

Two hundred paddlers will weave through the waters, their canoes carving a thin line in English Bay against the backdrop of Vancouver’s dramatic skyline.

When they pull in to Vanier Park – one of the many destinations on their 10-day journey – local chiefs from the Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations will greet them and offer permission to step ashore on to their traditional territories.

The protocol, which has played out on these lands for thousands of years, will be one of the signature events taking place next month as Vancouver marks the 150th anniversary of the signing of Canada’s confederation.

The milestone is being commemorated across the country this year. But as maple leaf-adorned paraphernalia flies off store shelves and the capital city of Ottawa prepares for thousands of tourists to attend Canada Day celebrations on 1 July, some Canadians have been questioning what, exactly, is being celebrated.

“Every single time I see a Canada 150 logo I want to take a Sharpie and add a couple zeros to the end of it,” Inuk filmmaker Alethea Arnaquq-Baril told a forum earlier this year. “Asking me to celebrate Canada as being 150 years old is asking me to deny 14,000 years of indigenous history on this continent.”

|

A rally in remembrance of the missing and murdered women and girls in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. ‘The celebration of the occupation of stolen land is really hard to wrap my head around.’ Photograph: Alamy |

The anniversary marks the year that the British North America Act was passed by the British parliament, paving the way for colonies of Canada – which included Ontario and Quebec – to join Nova Scotia and New Brunswick in creating a single Dominion of Canada.

In Vancouver, city officials initially considered boycotting the event, worried that honouring the country’s colonial past would compromise its efforts towards reconciliation with local First Nations.

Their concerns were well founded. “Everywhere I look right now I see every retailer and every store celebrating 150, but people really don’t have an understanding of what that means to indigenous people,” said Rhiannon Bennett of the Pulling Together Canoe Society. “The celebration of occupation of stolen land is really hard to wrap my head around. So we’re here looking at everyone celebrating 150 years of occupation and it’s hurtful.”

After consulting Aboriginal leaders, Vancouver instead launched Canada 150+, a rebrand that seeks to highlight indigenous history and culture.

Across Canada – where Canada 150 is being marked without the plus symbol – the anniversary has sparked myriad responses. Some, such as the elders of the Association of Manitoba Chiefs, have decided to boycott all events related to the anniversary, frustrated by a narrative that continues to exclude or marginalise what the association described as “Canada’s genocidal policies towards indigenous peoples”.

Others have sought to highlight what the past 150 years have meant to their communities, donning T-shirts that read Colonialism 150 or plastering the country with thousands of stickers that read Canada 150 Years of Genocide and Canada 150 Years of Broken Treaties.

“If you’re a conscious Canadian living in this country, you shouldn’t be supporting Canada 150,” said Jay Soule, an indigenous artist known as Chippewar who launched the sticker campaign earlier this year. “You can be proud to be a Canadian and live in this country, but you have to acknowledge the present day plight of indigenous people – as well as the past history – and not just sweep it under the rug.”

The passing of the act 150 years ago ushered in Canada’s first prime minister, John A Macdonald, who bragged that the indigenous population was being kept on the “verge of actual starvation” in order to save government funds. In 1920, Canadian bureaucrat Duncan Campbell Scott detailed to a parliamentary committee his desire “to get rid of the Indian problem.” He continued: “Our objective is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question, and no Indian department.”

His sentiment translated into the expansion of the church-run residential schools, which forcibly removed 150,000 Aboriginal children from their families. The schools, were rife with sexual and physical abuse, and were described as a tool of “cultural genocide” by a recent truth commission. In the 1940s, South African officials visited Canada to study the system of reserves and residential schools, taking home ideas to be incorporated into apartheid.

In some ways, little has changed, said Soule. “The same things are being done that were done 150 years ago, only with less blatant violence. We still have missing and murdered. Girls on a daily basis are still missing, still being murdered. We have mass incarceration, we have third world conditions, we have unsafe drinking water. The list going on and on and on.”

Ottawa is spending half a billion dollars to mark the anniversary, rankling some who point out that it has yet to comply with a 2016 ruling that it was racially discriminating against aboriginal youths by underfunding child welfare on reserves and has made little progress on promises to provide safe drinking water to the nearly 90 First Nations communities where inhabitants are advised to boil their water before drinking.

Along with repudiating the country’s collective amnesia, many activists have sought to highlight indigenous resilience and resistance. This week, dozens of groups across the country will take part in a National Day of Action – slated to coincide with the festivities of 1 July.

“We’re going to celebrate our survival,” said Russell Diabo of Defenders of the Land, a cross-Canada network of indigenous communities and activists. “It’s to celebrate our survival through racism and genocide – the policies of the government – but also to educate Canadians that we don’t have anything to celebrate when it comes to the British North America Act because that’s how the provinces stole our lands, territories and resources.”

Six months into the 150th anniversary year, there are indications that the message is sticking. The country’s most talked about the art exhibit, Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience by renowned artist Kent Monkman, has attracted tens of thousands of people as it takes on the country’s collective memory.

“There’s been a deliberate skating over and glossing over of the real history of this country,” said Monkman, who is of Cree ancestry. “And I wanted a very strong message for people – this year particularly – to not allow them to celebrate their country without really reflecting on the problems with their country’s founding myths.”

The exhibition at the Art Museum at the University of Toronto features nine chapters that delve into what the last 150 years have meant for Canada’s Indigenous peoples. “It’s not a pretty picture,” said Monkman.

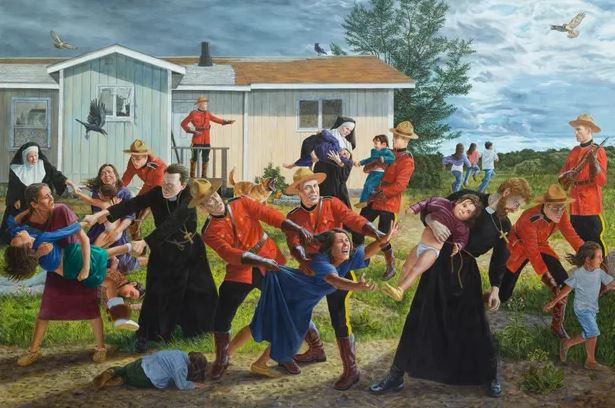

In one painting, the Royal Canadian Mounted Police join nuns in prying First Nations children away from their panicked parents, evoking the trauma of residential schools. Another features Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, Monkman’s alter ego, perched buck naked as she confronts the fathers of confederation as they carve up the land of her ancestors.

Part of the aim in creating Miss Chief was reverse the gaze of European settlers and reclaim the power to tell history, said Monkman. “It was really about making history paintings that could speak to the present but also authorise these histories into art history,” he added. “So that 150 years from now, people can look at those paintings and go, this is what happened.”