The Sabra and Shatila massacre of 1982 was one of the most significant milestones in Lebanon’s recent turbulent political history.

The Sabra and Shatila massacre of 1982 was one of the most significant milestones in Lebanon’s recent turbulent political history.

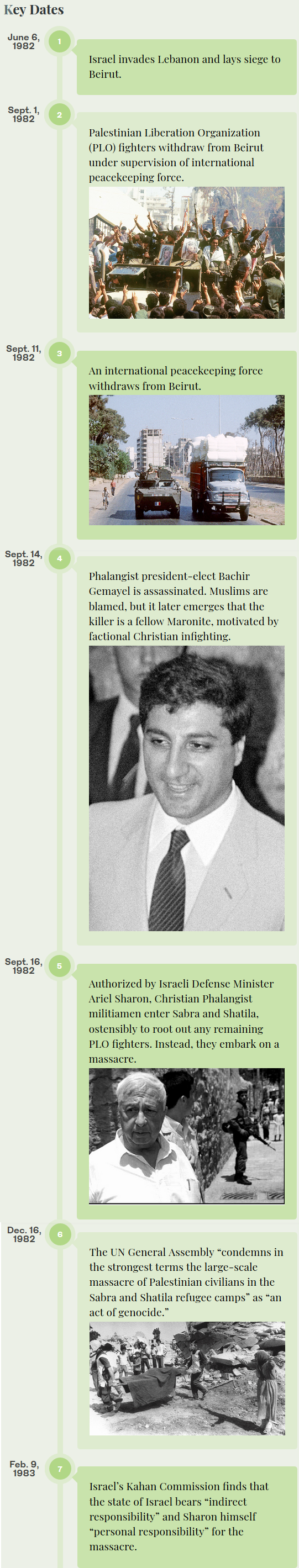

In that massacre, a force from a Lebanese Christian right-wing militia entered the south Beirut neighborhood of Sabra and the nearby Shatila Palestinian refugee camp and murdered hundreds of people (some sources claim more than 3,000), mostly civilian Palestinians and Muslim Lebanese.

The militiamen entered the neighborhood — where many Palestinian leaders resided — and the camp when the Israeli occupation forces were already in control of the Lebanese capital following the invasion of 1982.

Some sources have recorded that, from approximately 6 p.m. on Sept. 16 to 8 a.m. on Sept. 18, the mass murders were carried out in plain sight of the Israeli forces. Indeed, sources have also claimed that the Christian militias were even “ordered” by the Israelis to “clear out” the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) fighters from Sabra and Shatila, as part of their advance into predominantly Muslim west Beirut. Later reports suggested that, while the Israelis had received reports of the atrocities, they took no action to prevent or stop them.

Coming at the height of the Lebanese Civil War, the massacre summed up several elements and shed light on the complex regional dimensions of the war.

Sectarianism has almost always been at the core of the conflicts that guided the changing maps and power balance in Lebanon. Even before the First World War defeat of the Ottoman Empire — of which present-day Lebanon was a part — the area of Mount Lebanon went through scattered sectarian confrontations, beginning in 1840 and culminating in 1860 in massacres that led to a French military intervention. However, the reaction of the Ottomans was decisive in containing the French advance, and so were the joint efforts of major European powers.

The political outcome was the creation of the autonomous Mount Lebanon district in 1861. It was governed by a Christian Ottoman official, whose appointment would be ratified by the European powers. But, after the defeat of the Ottomans in the First World War, the Paris Peace Conference of 1920 annexed several areas to Mount Lebanon, including Beirut, as well as putting the new enlarged Lebanon under French Mandate.

In the new Lebanon, the Christian-majority population of Mount Lebanon was hugely diluted as a result of the annexation of major Sunni and Shiite cities and areas. However, the Christians felt that the French Mandate would be enough for them to dominate the political scene. That assumption was proven wrong, however, especially following Lebanon’s independence in 1943. By then, the three Muslim sects (Sunnis, Shiites and Druze) had become, by many estimates, a clear majority. Furthermore, the tide of Arab nationalism rose as a result of the Palestinian “Nakba” in 1948, which rapidly radicalized Arab politics. The Palestinian refugee problem added to grievances in host countries like Lebanon and Jordan.

Radicalization was further enhanced by the Arab defeat of June 1967, which gave rise — as well as enormous credibility — to the Palestinian resistance movement (the “feda’yeen”). Later, in the fall of 1970, following battles between the feda’yeen and the Jordanian army, the Palestinian resistance movements switched their headquarters from Amman to Beirut.

Lebanese Muslims, Arab nationalists and leftist leaderships stood by the Palestinians and made common cause with them. On the other side, the Christian political elites and masses became apprehensive that the emerging alliance posed a deadly threat to their dominant position and, subsequently, the country’s regime, identity and sovereignty.

I lived through those days and remember them well. In 1973, the Christian-led Lebanese Army attempted to contain the feda’yeen’s power in the camps, but the Muslim-leftist uproar against the army paved the way for the imminent civil war. Soon enough, the Christian militias were being openly armed and trained by some army officers, while leftist and Arabist militias secured arms and training through the Palestinians and some Arab regimes.

The war broke out in 1975 and continued, through different phases, until 1990.

The Israeli invasion in June 1982 was intended to finish off the Palestinian military and political infrastructure, and establish a “friendly” regime in Beirut. This was done by militarily forcing the Palestinian resistance movements out of Lebanon and handing the Lebanese presidency to Bachir Gemayel, leader of the Lebanese Forces, the most powerful Christian militia, in August 1982. Gemayel, however, was assassinated on Sept. 14, before taking the oath of office. His assassination in a major explosion in Beirut shocked the Christians and enraged their militias, which retaliated by attacking Sabra and Shatila just two days later.

By this time, the Arab world was weak and deeply divided following Egypt’s recognition of Israel, which resulted in an Arab boycott. The Israelis were, thus, able to collude in this massacre without fearing any substantial Arab reaction. In fact, it was the global furor against the massacre that led, in 1983, to the establishment of a commission chaired by Sean MacBride, the assistant to the UN secretary-general and president of the UN General Assembly at the time. The commission concluded that Israel, as the camp’s occupying power, bore responsibility for the violence, and that the massacre was a form of genocide.

The reaction against the massacre was strong, even in Israel itself. Also in 1983, the Kahan Commission was appointed to investigate the incident. It found that Israeli military personnel, despite being aware that a massacre was in progress, had failed to take serious steps to stop it. The commission also deemed Israel indirectly responsible, and that Defense Minister Ariel Sharon bore personal responsibility “for ignoring the danger of bloodshed and revenge,” thus forcing him to resign.