Seventy years ago, American researchers infected Guatemalans with syphilis and gonorrhea, then left without treating them. Their families are still waiting for help.

Frederico Ramos was 22 when he left his home in San Agustín Acasaguastlán, Guatemala, in 1948 to serve in the country’s military. He didn’t want to go, but service was all but mandatory. Buses often came to his town to take young men away. Resisting once would just mean being picked up the next time. So he gritted his teeth and made the trip to Guatemala City, about two hours southwest. He worked for 30 months in the Guatemalan air force. He spent long days on guard duty watching over planes at the base.

Once his service was complete, Ramos moved to La Escalera, a tiny village of 400 people near his hometown where he could plant beans and corn and start his own family. Soon after settling down, he began suffering from what he refers to as “bad urine”—he felt extreme strain when he relieved himself. Over the years it got much, much worse and extended beyond his genitals to his appendix and other organs. He consulted doctors who prescribed medicines that didn’t work. “They were just taking our money,” he said. Instead, he treated himself with tea made from the fruit of guapinol trees (known for its analgesic properties). Mostly, he learned to live with the pain.

As his eight children grew up, they too started to have similar health problems. And later on, so did their children. His son Benjamin, for instance, also has intense pain when he needs to urinate. It stings so badly he has to sit down and breathe to gather the strength to walk home from the fields. Benjamin’s son Roheli has health problems that seemed related but were different: He grew up with an ache in his joints, particularly his knees. A fan of Real Madrid, he tried to play soccer with other local boys but often ended up falling spontaneously and crying. One of Benjamin’s nieces is barren. Benjamin’s grandsons Eduardo and Christian have such crippling leg pain that they can hardly focus on their schoolwork.

For years, the family didn’t know what they were suffering from. A friend of theirs, who was studying at a university in the city, eventually looked up their symptoms and said it seemed like gonorrhea. A textbook explained one sign of the disease is a burning feeling during urination. In severe cases, gonorrhea is known to damage reproductive organs. An infected woman could also pass it on to her children, which could result in joint infections, blindness, or a life-threatening blood infection. The diagnosis made sense, but being as poor and remote as they were, the family couldn’t find a treatment.

Frederico Ramos, age 91, and Benjamin Ramos, age 64.

Frederico Ramos, age 91, and Benjamin Ramos, age 64.

Carlos Duarte

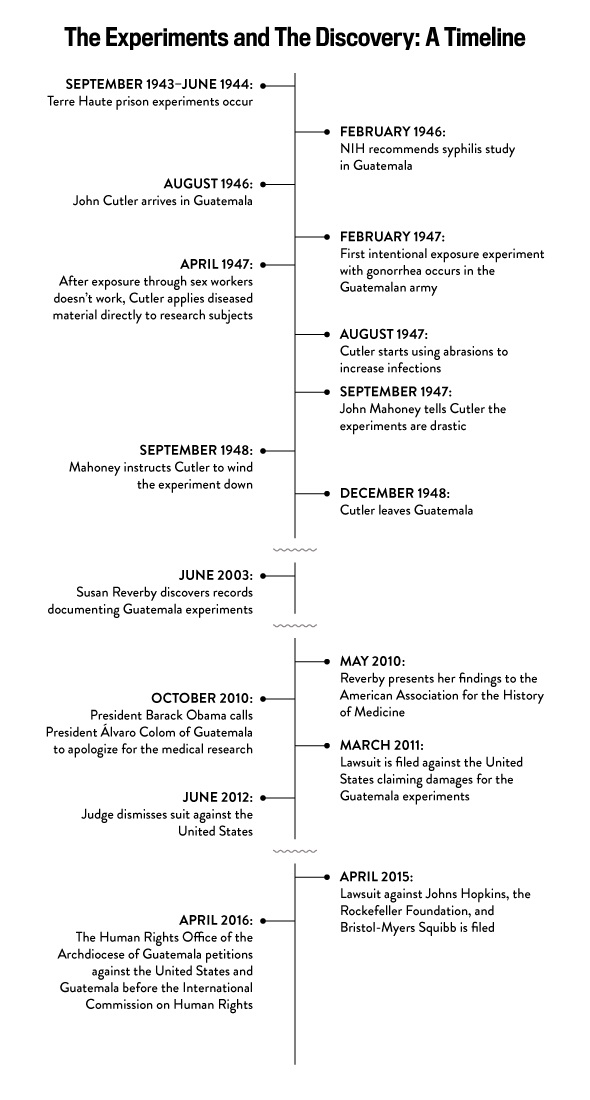

Frederico is now 91 years old. Sitting on a chair outside his son Benjamin’s small home, the frail veteran tells me how in October 2010, he heard from friends about recent news reports in which the government announced that several members of the Guatemalan military had been secretly and intentionally infected with gonorrhea by American researchers in the 1940s. Other groups—mental patients and prisoners—had additionally been exposed to syphilis and chancroid.

The experiments were in the news because then–Secretary of State Hillary Clinton had issued a public apology to the government of Guatemala for violating its citizens’ human rights. Álvaro Colom, president of Guatemala when Clinton made reconciliation efforts, announced an investigation into the matter. Then-President Barack Obama asked the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues to commence a report investigating how these horrifying experiments came to be. The report has been completed, the apology long since issued. But for families like Frederico’s, compensation and treatment has still not come.

Clinton’s apology was spurred by the experiments’ discovery—made by Susan Reverby, a historian at Wellesley College, in 2003. Reverby had been researching the Tuskegee experiments, perhaps the most famous example of a breach of medical ethics in the United States. In those experiments, black men who had already contracted syphilis had been told they were being treated when they were actually receiving placebos as part of an experiment on the effectiveness of treatment. All the while, these men were being observed by doctors interested in learning how their bodies would degrade from the illness. When the reality of the experiment became clear, in the 1970s, it was immediately stopped and a major lawsuit was filed.

It turns out that one of the key researchers who participated in the Tuskegee study in the 1950s had previously done experimentation studying sexually transmitted diseases in Guatemala. This research had a similar goal—to understand the effect syphilis and other sexually transmitted diseases had on the body, and to test whether existing treatments were effective—but the methods used were even more egregious than what happened in Tuskegee.

Work Projects Administration Poster Collection. Date stamped on verso: March 27, 1940.

Library of Congress

The experiments came to be because during World War II, American researchers were consumed with trying to prevent and cure gonorrhea and syphilis. These diseases affected the general public but they were especially a drain on manpower in the military. According to one 1943 government correspondence, new infections with gonorrhea were said to cost the Army 7 million working days each year, “the equivalent of putting out of action for a full year the entire strength of two full armored divisions or of ten aircraft carriers.” The cost of treating these infections was somewhere around $34 million, and the most-used treatment was understudied and often ineffective. (It also caused burning upon application, which made compliance limited.)

Given the circumstances, government researchers decided they had to test a prophylactic medication: a measure to prevent these diseases in people who had been exposed to them. The only problem was that testing a prophylaxis would require them to introduce the diseases to previously unexposed human subjects. The National Research Council’s Subcommittee on Venereal Diseases agreed it was scientifically important to do this kind of testing, though it recognized it might not be popular in public opinion. To conform to ethical standards, judged by a team made up mostly of doctors, only volunteers who were told about the risks and who provided their informed consent could be used.

The group concluded that the experiment would be best conducted at a prison. A psychiatric facility was considered a potential study site, but it was ruled out because its patients wouldn’t be able to properly consent. Military personnel were also rejected because they couldn’t be kept sexually isolated. (It was not uncommon, at the time, to use prisoners for all kinds of medical research.) Overseers of the project believed prisoners might participate out of patriotism, a chance away from the boredom of prison life, or because they might be unconcerned about the risks. But the real reason they would participate was obvious: Though experimenters could not promise pardons or commutations of sentences to encourage participation, they could pay them $100 for volunteering.

Dr. John F. Mahoney, assistant chief of the Public Health Service Venereal Disease Research Laboratory in Washington, headed the project and worked with Dr. John Charles Cutler, a 28-year-old new member of the Public Health Service. The plan was to expose prisoners at Terre Haute, a federal prison in Indiana, to bacteria that caused gonorrhea and then give them a prophylactic agent to prevent them from contracting the disease. Within 10 months, they realized their plan was a bust. Before testing a prophylaxis, the experimenters first had to first show they could in fact infect patients. They deposited several strains and concentrations of gonorrhea on subjects’ sex organs, but they couldn’t seem to produce infections. So they gave up. They concluded that there must have been something about the act of sex that made gonorrhea easier to transmit, and they couldn’t exactly test that in a lab setting—at least not in Indiana, where prostitution was illegal.

By the time the Terre Haute experiment was already underway testing preventative measures, penicillin was becoming more widely recognized as an effective cure for sexually transmitted diseases. Mahoney, in fact, was one of its leading advocates and reported as such in Time magazine. But there were still many remaining questions about penicillin: Could it be used again if a patient was reintroduced to the same or different strains? Did it just provide immediate relief or cure the disease? And could penicillin be applied preventatively after exposure?

These questions needed to be tested, particularly the last one. The idea to go to Guatemala to do so came to Mahoney’s assistant Cutler through his relationship with Dr. Juan Funes, a Guatemalan physician who had previously worked as a fellow with Mahoney and other researchers involved with Terre Haute. Funes believed that the legality of sex work in Guatemala, along with the required twice-a-week health inspections for the workers, would help to create a controlled study environment in that country, bolstered by the fact that the country had a very low rate of gonorrhea and syphilis. This time, the research received approval and funding from the deputy surgeon general and the same National Institutes of Health group that approved the study at Terre Haute prison.

Cutler intended to conduct his work in a prison setting, just as he had in the U.S. He arrived in Guatemala in August 1946. It was a time of enormous change for the country, which had its first democratically elected leader following a coup that ended a decades-long dictatorship. The new government was hoping to foster relations with the United States. Cutler became part of this: He spent his first few months building goodwill by helping to build labs, training physicians, and providing supplies. In exchange, he gained access to institutions across the Guatemalan government—the military, orphanages, mental health centers, and of course, prisons.

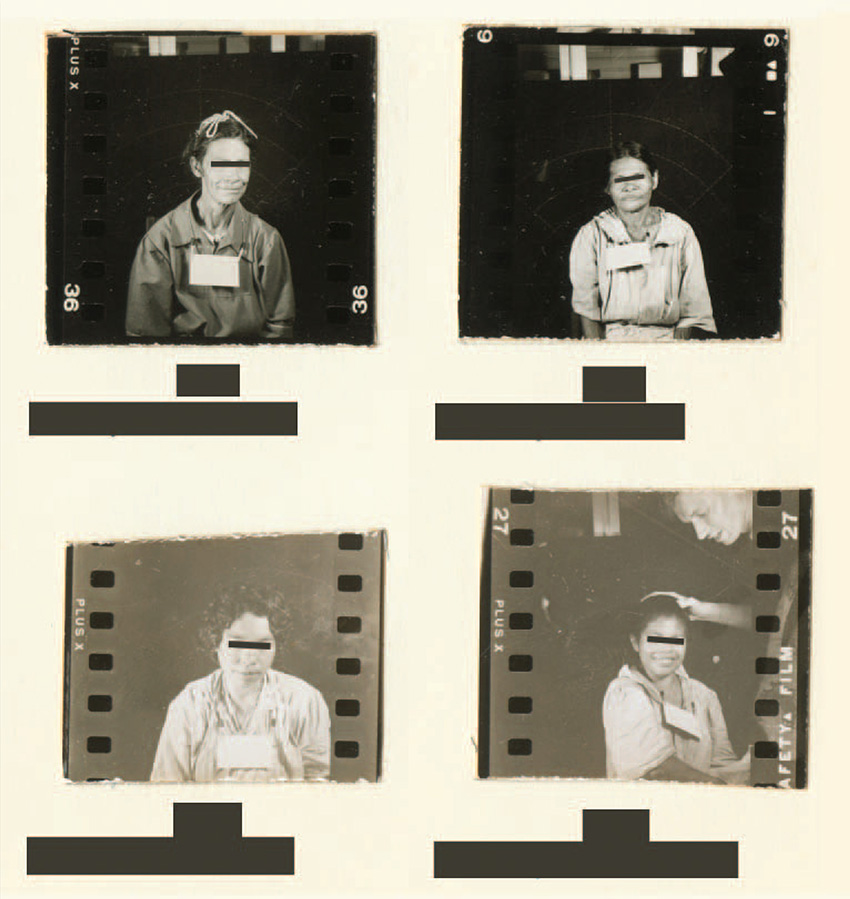

Female patients from the Guatemalan psychiatric hospital who were exposed to syphilis as part of the experiments conducted by Cutler between 1946 and 1948.

National Archives and Records Administration

Six months after Cutler arrived in Guatemala, he began his intentional exposure experiments within the Guatemalan army. He also thought he would try a way to get around the trickiness of infecting the men: prostitutes. In one early study, he infected prostitutes by moistening a cotton swab with pus carrying gonorrhea bacteria and inserting it into their genitals “with considerable vigor.” There is no evidence they were informed about the risk. All of them contracted the disease.

He then had them have sex with the men he wanted to study, first prisoners and then the army. (He had switched from prisoners to the army after realizing that despite being plied with free sex workers and alcohol, many prisoners believed they were growing weaker because of blood draws.) Army men were often lubricated with alcohol, too, before being set up with the prostitutes. The women were asked to have sex with multiple men in a row. In one case, one prostitute had sex with eight soldiers in a period of 71 minutes. The soldiers were never informed that this was part of a medical experiment, obliterating any possibility that consent was obtained and making the experiments ethically unsound.

Cutler knew that his experiments might be frowned upon back home. The same month he began his intentional exposure work with the Guatemalan army, he received a letter from a colleague that said Surgeon General Thomas Parran Jr. was particularly interested in the experiment, though Parran had also acknowledged that the same type of research couldn’t be done in the United States. A New York Times article from around this time, on other venereal disease research done by a team member, mentioned how useful it might be to test prophylaxis on human subjects but said such experiments would be “ethically impossible.” In a letter to Mahoney, Cutler wrote that they should maintain a level of secrecy about the project: “We are just a little bit concerned about the possibility of having anything said about our program that would adversely affect its continuation.”

These statements make it clear that this web of onlookers knew that some people might see Cutler’s studies as problematic, but the truth was that research norms were still ambiguous at the time. The Nazi doctor trials in Nuremberg, Germany, were taking place concurrently, so it was a pivotal period when the rules surrounding the ethics of human experiments had yet to be solidified. A Guatemalan report on the program shows that per the country’s penal code, it was a crime to purposely transmit a venereal disease to another person. Doctors who knew their patients were infected and did nothing to prevent transmission were considered accessories to the crime at the time. But still, the Guatemalan physicians and authorities in the Ministry of Health who knew about it also failed to do anything to stop it.

Meanwhile, Cutler’s experiment using the prostitutes ultimately didn’t accomplish much beyond infecting the women: None of the men contracted gonorrhea. (Some of Cutler’s superiors in the U.S. speculated this might have been due to the speed of the intercourse.) In the face of failure from the prostitute approach, Cutler soon moved back to artificial inoculation—with modifications. At first, he placed infected biological material on the surface of subjects’ genitals as he had in Terra Haute. But then he started to perform “deep inoculation,” inserting the pus deeper into patients’ urethras. Rates of infection quickly escalated.

Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues/National Archives and Records Administration

Mahoney sent Cutler a letter expressing concern about whether the research was worth continuing if sexual intercourse wasn’t working as a means of infection, but Cutler convinced him it was worthwhile to press on. There was no way they could perform their planned experiments if they couldn’t consistently produce an infection, he argued. Though supervisors back home expressed disapproval at times, ultimately they agreed to restrict their conversations about it to avoid derailing the project. They allowed Cutler to include just the barest of facts on his progress.

Cutler’s research methods only became more extreme. He expanded his work to the penitentiary as well as the Asilo de Alienados, the country’s only psychiatric hospital. He injected subjects with bacteria for gonorrhea and syphilis. Cutler placed gonorrhea bacteria on patients’ eyes to infect them. The experimenters scraped men’s penises with hypodermic needles and then dressed their abrasions with syphilitic material. Women were told to swallow syphilitic solutions. Sometimes, infected pus was injected into their spinal cords.

In a particularly gruesome case, a patient named Berta was injected in her left arm with syphilis. More than a month later, she started to develop small red bumps around her injection site, and then she started to develop lesions on her limbs. She was given treatment three months after her injection, but by about three months later, Cutler wrote in his research notes that it looked like she was going to die. The same day he wrote the note, experimenters put gonorrhea pus in her eyes and re-infected her with syphilis. Her eyes soon filled with discharge, and she began bleeding from her urethra. Days later, she died. There were several other case studies of patients who died following their involvement in the studies.

Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues/National Archives and Records Administration

Just months into Cutler’s experiments, interest in prophylaxis was already waning at home, since penicillin was such an effective cure that rates of transmission were declining. In February 1948, the surgeon general that had originally supported the work was replaced, and Mahoney wrote to Cutler saying that they had “lost a very good friend” and that it was time to “get our ducks in line.” After a few more months, Cutler concluded his research and returned home. He left one American researcher and some of his partners in Guatemala to continue some of his projects. Certain patient groups continued to be monitored, and some of them continued to test positive for STDs. It’s unclear if they were given treatment. Though Cutler wrote up his findings in reports in 1952 and 1955, they were never peer reviewed or published. None of the other collaborators on the project included it in official reviews of their STD research.

Cutler went on to have a successful, if eventually clouded, career. He took on various jobs and then went on to become a primary researcher in the Tuskegee experiments—and one of its staunchest defenders. (His testimony appears in PBS’s 1993 Nova film The Deadly Deception about the study.) He ultimately became the acting dean of the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh. When he died in 2003, his papers were given to the archives of the school.

Reverby found them that same year. She stumbled on them due to her interest in Thomas Parran Jr., who had been surgeon general prior to and during the start of the Tuskegee Syphilis Study and later served as dean of the Graduate School of Public Health at the University of Pittsburgh, a position Cutler had also briefly held. An archivist at the university’s library directed her to the papers. Cutler, Reverby knew, had been involved in the Tuskegee experiments in the 1950s. Most of what she found in this dossier was the Guatemala material.

She took her findings, along with the original papers, to a former director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention who also found the experiments disturbing. From there, the revelations made their way up the chain of command at the White House. When the Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues completed a report on the project in September 2011, it was titled “Ethically Impossible,” and it outlined, as above, the narrative of the study and how unconscionable the actions were, even at the time. Of the 1,308 subjects known to have been exposed to an STD, only 678 were documented to receive treatment.

Holly Allen

Even before the report came out, lawyers had started mobilizing to seek compensation for the Guatemalan victims. In March 2011, the U.S. government was hit with a class-action lawsuit on behalf of the Guatemalan families affected by the experiments. It blamed officials from the United States Public Health Service and the Pan American Sanitary Bureau, now the Pan American Health Organization, for subjecting people to experiments without consent. The victims were seeking damages to their livelihood and money for medical treatment. Most were living in extreme poverty.

But the case was quickly dismissed under a principle called sovereign immunity. This legal barrier essentially allows the United States to state that it won’t allow itself to be sued by a foreign government. Sovereign immunity exists as a way to protect the public’s pocketbook—it prevents the United States from being subjected to politicized lawsuits to challenge its foreign policy, for example.

In April 2015, a second suit was filed targeting instead private entities that had various roles in the research, namely Johns Hopkins University, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the pharmaceutical company Bristol-Myers Squibb. The complaint was filed under the Alien Tort Statute, a law under which foreigners can bring claims in federal court for alleged violations of international law. This case is ongoing. Federal Judge Marvin J. Garbis has already said in hearings that the research was abhorrent and violated ethical standards.

But there are three other main questions that are left to be resolved. The first is whether these private entities were involved enough in the research to be said to have colluded in its design and the secrecy around it, as the complaint argues they are. The case the prosecutors are building states that the institutions were central to the research or at the very least aware of the situation. It states that “from 1945-1956, physicians, researchers, and other employees and agents of Johns Hopkins, The Rockefeller Foundation, and Bristol-Myers Squibb designed, developed, approved, encouraged, directed, oversaw, and aided and abetted nonconsensual, nontherapeutic, human subject experiments in Guatemala.”

Presidential Commission for the Study of Bioethical Issues

It describes professors as leaders of Johns Hopkins who were deeply involved in the design of the experiments: “These men—who now have their names on buildings on Johns Hopkins’ campuses—designed, developed, directed, oversaw, implemented, and aided and abetted the Guatemala Experiments.” Parran was both a member and trustee of the Rockefeller Foundation at the time, and the complaint states that he “committed The Rockefeller Foundation and its staff and resources to the Guatemala experiments.” According to the complaint, Bristol-Myers Squibb had an interest in the experiments on account of how much cheaper it would be to test penicillin’s effectiveness in Guatemala, and the complaint describes the company as “putting the companies’ interests and financial gains above the lives and well-being of the Guatemalan test subjects and their sexual partners, wives, children, and grandchildren.”

Lawyers from Johns Hopkins and the other defendants have replied to the accusations by stating that while the experiments were “deplorable,” they shouldn’t be held liable for the actions. A spokesperson from Johns Hopkins wrote that “the study in Guatemala was initiated, funded and conducted by the U.S. Government with the cooperation of Guatemalan officials, not by Johns Hopkins.” Bristol-Myers Squibb echoed this sentiment, stating, “No one is condoning what happened in the Government-run Guatemala Experiments 70 years ago, however we believe this lawsuit lacks merit and have filed a motion to dismiss which is pending.”

A spokesperson from the Rockefeller Center went perhaps further, stating:

The research conducted in Guatemala was morally repugnant and the Rockefeller Foundation wholeheartedly agrees with U.S. District Judge Reggie Walton that the United States Government owes reparations to the victims and their families for the damage it caused. The Rockefeller Foundation did not design, fund, or manage any of these experiments, and had absolutely no knowledge of them. That’s why the U.S. Presidential Commission, put in place to investigate the matter, placed full responsibility with the U.S. Public Health Service without ever mentioning the Rockefeller Foundation.

Everyone agrees that the experiments occurred and were unethical—the legal question is who should be held responsible.

The second issue of significance is the statute of limitations on the claims brought by the Guatemalan victims and their families—and whether it has already run out. It’s unclear whether the patients will get some relief on such a statute, because they didn’t know what had happened to them, given that the facts underlying the research program remained concealed for so long.

The final complicating factor: Even though many of the plaintiffs have been diagnosed with syphilis or gonorrhea, it’s difficult to prove definitively that they contracted it from the experiments. Decades have passed since the experiments were conducted, making it almost impossible for the participants to prove that their health condition didn’t come from somewhere else, such as a sexual partner. For example, when Frederico heard about the experiment from the news coverage, he immediately remembered American doctors examining him and giving him injections during his time in the Guatemalan air force. He recalls being given money to see prostitutes by some of his supervisors after these visits. But he doesn’t have solid proof that this is where his infection came from.

There are 842 people in the class-action suit, each of whom will have to present their case before a jury. (Frederico is one of them: He got in touch with the lawyers after speaking to a local journalist about his memories and ailments.) Last September, Judge Garbis dismissed the case and requested the plaintiffs’ lawyers resubmit it with more detailed examples of the stories they might present. The amended complaint was submitted in December. The defendants’ lawyers submitted a motion to dismiss on Feb. 17. Now the plaintiffs’ lawyers are being given a chance to respond. As the case proceeds, Frederico and others like him continue to suffer the aches and pains associated with their diseases.

In December 2015, the Archdiocese of Guatemala’s Human Rights Office, represented by the International Human Rights Clinic at the University of California Irvine School of Law and other parties, filed a petition with the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights asking it to rule that the experiments violated the customary international law on human rights, the American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man, and the American Convention on Human Rights—and that those affected have the right to seek remedy. The Inter-American Commission, which interprets and applies the declaration and convention along with customary international law, is an organ of the Organization of American States, which brings together all 35 nations of the Americas.

Both the American and Guatemalan governments have agreed to the declaration, though only Guatemala has agreed to the convention. The petition provides yet another road for Guatemalan victims to seek justice, but the problem is that neither the declaration nor the convention is a binding law. “As far as the United States is concerned, there are so many human rights instruments it has made commitments to that it doesn’t really follow up on,” said Bethany Spielman, director of the medical ethics program at the Southern Illinois University School of Medicine, explaining why this might not be legally binding.

Many legal experts have suggested that the most expedient way to provide reparations to Guatemalan victims is through legislation rather than litigation, perhaps via a public fund such as the one for victims of Tuskegee or 9/11 first responders. But since the abuses occurred abroad, and the United States doesn’t have a large population of Guatemalans to fight for these victims, such a result is unlikely. Another barrier is the seeming lack of commitment to international aid by President Donald Trump.

George Annas, director of the Center for Health Law, Ethics & Human Rights at the Boston University School of Public Health, believes that the delay in providing help to Guatemalan victims of the research is a travesty. “We need to show that we have a responsibility for all of our researchers,” Annas says. “People know we can’t just forget about it, and it’s important. Litigation is being pursued because right now it’s the only way, and it’s clunky.”

“They knew these people didn’t know how to read or write”

—Benjamin Ramos

Annas believes that the actions we take to compensate these victims are particularly important in the context of how much medical research is done abroad today. In the immediate post–World War II era, international research trials were the exception, but today they have become the rule. A 2009 study, for example, concluded that in 2007, a decade ago, more than one-third of the trials sponsored by the 20 largest U.S.-based pharmaceutical companies were being conducted outside of the United States. Annas says the percentage has only increased since then. The reason seems to be primarily financial, and ethical oversight is a “major concern,” the study concluded. Some of these trials are conducted in countries that have their own research oversight, but the majority is conducted in countries where the oversight is problematic at best.

It’s true that in the intervening decades since the Guatemala study, modern safeguards, such as requirements of transparency and accountability, have been added to processes for government research. But they are absent in much of the research done by private companies, and oversight of this type of research is increasingly conducted by other private companies rather than government or academic bodies. Annas argues that consent forms have taken the place of a meaningful consent process, having been reduced to a necessary paperwork. “We have taken research out of the prisons and mental institutions, but have substituted poor people in developing countries as ‘go to’ subjects,” Annas said. “Informed consent tends to become even more marginalized in an international setting.”

Families like Frederico’s are still unable to comprehend how it all happened. “They knew these people didn’t know how to read or write,” Benjamin, Frederico’s son, said. “It was so much easier to take advantage of people who don’t know what’s going on, who don’t have any clue. They knew they could get away with it.”

Annas points to two major examples from the 1990s that explain why the Guatemala example is so threatening to those conducting research—it could set a precedent that would force the U.S. to compensate other victims of unethical research, which could get expensive. In one case, the United States conducted experiments on pregnant women infected with HIV in Africa, Thailand, and the Dominican Republic. Some were given drugs to try to prevent transmission of the virus to their children before or during childbirth while others were given placebos. The NIH and the CDC, which paid for the study, were attempting to determine if they could lower the dosage of the drugs in the developing world to make the drug regimen cheaper to pay for. A more complicated prevention protocol was thought to be too expensive to use in the developing world. About 1,000 babies were believed to have contracted HIV/AIDS during the experiment, which was discontinued early because of the controversy surrounding the use of a placebo and lack of informed consent.

Carlos Duarte

Another case shows the importance of obtaining proper consent when conducting a trial. During a 1997 epidemic, the drug company Pfizer was testing the effectiveness of the new meningitis antibiotic Trovan (trovafloxacin) on children in Nigeria. Pfizer treated about 100 Nigerian children with Trovan as part of its effort to determine whether the drug, which had never been used on children in its oral form, would be an effective treatment for the disease. Pfizer treated about 100 other children with ceftriaxone, the gold standard for meningitis treatment. During the trial, 11 children died, five on the new drug and six while taking the old drug, indicative of the seriousness of the disease. But Pfizer had not received proper consent from the parents of the children who participated in the trial, prompting a lawsuit that Pfizer settled out of court.

“Most people think we don’t conduct trials this way,” Annas said. “We always act shocked by research scandals and see them as historical anomalies that cannot be repeated. But so far, we’ve always been wrong.”

In 2011, the presidential commission for the same bioethics commission that completed the Guatemala syphilis report also published a report on international research. It recommended that the country develop a compensation system perhaps akin to the U.S. National Vaccine Injury Compensation Program—which covers people harmed by certain vaccines—for people who are injured as test subjects in research. The site hosting that report, bioethics.gov, is no longer in service: A note on the archived site says that it will stop being updated as of Jan. 15, 2017, likely in anticipation of the presidential transition.

In addition to providing compensation to victims, the advisers on the Archdiocese of Guatemala’s petition are also advocating for sharpening the teeth of laws that protect research subjects internationally. They suggest amendments to the Common Rule, the set of guidelines used by institutional review boards overseeing research involving human subjects in biomedical and behavioral research in the United States and internationally. They have sent comments to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services saying the Common Rule should provide a stronger and more specific definition of informed consent, especially in autocratic countries where consent can never really be voluntary or in developing countries that see being involved in American experiments as a sign of prestige—or as necessary to obtain aid. The comments also recommend that the United States waive sovereign immunity in cases involving medical experimentation and require treatment and compensation for research-related injury, which could hypothetically reopen the door to compensation for the Guatemala experiments from the U.S. government.

Carlos Duarte

It’s hard to predict how long it will take for the legal cases to reach a conclusion. The John Hopkins case will likely not come before a judge until April or May, the defendants’ lawyers working on it say. After that, what could follow is either a round of appeals or a process of discovery. Both processes can be lengthy. It’s also unclear when the Inter-American Commission will respond to the petition, since it has wide jurisdiction over what issues it handles and when. While Obama and Clinton said they were shocked and disgusted by the experiments when they first found out about them, they did not publicly discuss them after the bioethics commission completed its report. Trump has not yet mentioned the trial.

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS