Activist Israel Kaunatjike journeyed from Namibia to Germany, only to discover a forgotten past that has connections to his own family tree

Activist Israel Kaunatjike journeyed from Namibia to Germany, only to discover a forgotten past that has connections to his own family tree

As a teenager in the 1960s, Israel Kaunatjike joined the fight against apartheid in his native Namibia. He couldn't have known that his activism would take him across the globe, to Berlin—the very place where his homeland's problems started.

Back then, Europeans called Kaunatjike’s home South-West Africa—and it was European names that carried the most weight; tribal names, or even the name Namibia, had no place in the official taxonomy. Black and white people shared a country, yet they weren't allowed to live in the same neighborhoods or patronize the same businesses. That, says Kaunatjike, was verboten.

A few decades after German immigrants staked their claim over South-West Africa in the late 19th century, the region came under the administration of the South African government, thanks to a provision of the League of Nations charter. This meant that Kaunatjike's homeland was controlled by descendants of Dutch and British colonists—white rulers who, in 1948, made apartheid the law of the land. Its shadow stretched from the Indian Ocean to the Atlantic, covering an area larger than Britain, France, and Germany combined.

“Our fight was against the regime of South Africa,” says Kaunatjike, now a 68-year-old resident of Berlin. “We were labeled terrorists.”

During the 1960s, hundreds of anti-apartheid protesters were killed, and thousands more were thrown in jail. As the South African government tightened its fist, many activists decided to flee. “I left Namibia illegally in 1964,” says Kaunatjike. “I couldn't go back.”

He was just 17 years old.

Kaunatjike is sitting in his living room in a quiet corner of Berlin, the city where he's spent more than half his life. He has a light beard and wears glasses that make him look studious. Since his days fighting apartheid, his hair has turned white. “I feel very at home in Berlin,” he says.

| Israel Kaunatjike has lived in Berlin for most of his life. (Daniel Gross) |  |

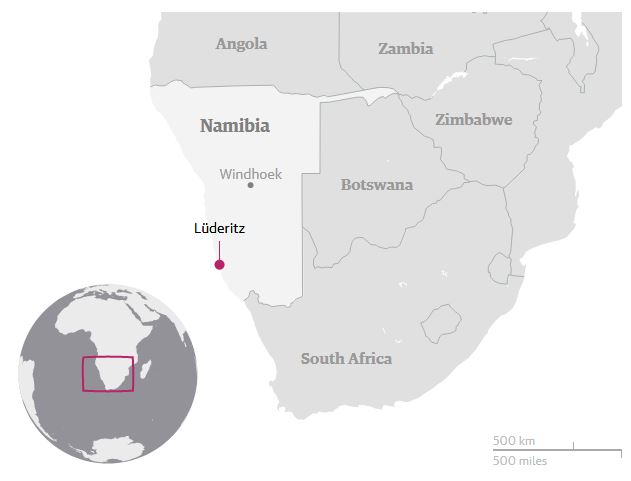

Which is a bit ironic, when you consider that in the 1880s, just a few miles from Kaunatjike's apartment, the German Kaiser Wilhelm II ordered the invasion of South-West Africa. This makes his journey a strange sort of homecoming.

The battle that Kaunatjike fought as a teen and arguably still fights today, against the cycle of oppression that culminated in apartheid, began with a brutal regime established by the German empire. It ought to be recognized as such—and with help from Kaunatjike, it might.

Germans first reached the arid shores of southwestern Africa in the mid-1800s. Travelers had been stopping along the coast for centuries, but this was the start of an unprecedented wave of European intervention in Africa. Today we know it as the Scramble for Africa.

In 1884, German chancellor Otto von Bismarck convened a meeting of European powers known as the Berlin Conference. Though the conference determined the future of an entire continent, not a single black African was invited to participate. Bismarck declared South-West Africa a German colony suitable not only for trade but for European settlement. Belgium's King Leopold, meanwhile seized the Congo, and France claimed control of West Africa.

The German flag soon became a beacon for thousands of colonists in southern Africa—and a symbol of fear for local tribes, who had lived there for millennia. Missionaries were followed by merchants, who were followed by soldiers. The settlers asserted their control by seizing watering holes, which were crucial in the parched desert. As colonists trickled inland, local wealth—in the form of minerals, cattle, and agriculture—trickled out.

Indigenous people didn't accept all this willingly. Some German merchants did trade peacefully with locals. But like Belgians in the Congo and the British in Australia, the official German policy was to seize territory that Europeans considered empty, when it most definitely was not. There were 13 tribes living in Namibia, of which two of the most powerful were the Nama and the Herero. (Kaunatjike is Herero.)

|

|

|

Germans were tolerated partly because they seemed willing to involve themselves as intermediaries between warring local tribes. But in practice, their treaties were dubious, and when self-interest benefitted the Germans, they stood by idly. The German colonial governor at the turn of the 20th century, Theodor Leutwein, was pleased as local leadership began to splinter. According to Dutch historian Jan-Bart Gewald, for instance, Leutwein gladly offered military support to controversial chiefs, because violence and land seizure among Africans worked to his advantage. These are all tactics familiar to students of United States history, where European colonists decimated and dispossessed indigenous populations.

When Kaunatjike was a child, he heard only fragments of this history. His Namibian schoolteachers taught him that when the Germans first came to southern Africa, they built bridges and wells. There were faint echoes of a more sinister story. A few relatives had fought the Germans, for example, to try and protect the Herero tribe. His Herero tribe.

Kaunatjike's roots are more complicated than that, however. Some of his relatives had been on the other side—including his own grandfathers. He never met either of them, because they were both German colonists.

| This illustration depicting a German woman being attacked by black men was typical of what Germans would have been told about the Herero genocide: that white citizens, women particularly, were in danger of attack (Wikimedia Commons) |  |

“Today, I know that my grandfather was named Otto Mueller,” says Kaunatjike. “I know where he's buried in Namibia.”

During apartheid, he explains, blacks were forcibly displaced to poorer neighborhoods, and friendships with whites were impossible. Apartheid translates to “apartness” in Afrikaans. But many African women worked in German households. “Germans of course had relationships in secret with African women,” says Kaunatjike. “Some were raped.” He isn't sure what happened to his own grandmothers.

After arriving in Germany, Kaunatjike started to read about the history of South-West Africa. It was a deeply personal story for him. “I was recognized as a political refugee, and as a Herero,” he says. He found that many Germans didn't know their own country's colonial past.

But a handful of historians had uncovered a horrifying story. Some saw Germany's behavior in South-West Africa as a precursor of German actions in the Holocaust. The boldest among them argued that South-West Africa was the site of the first genocide of the 20th century. “Our understanding of what Nazism was and where its underlying ideas and philosophies came from,” write David Olusoga and Casper W. Erichsen in their book The Kaiser's Holocaust, “is perhaps incomplete unless we explore what happened in Africa under Kaiser Wilhelm II.”

Kaunatjike is a calm man, but there's a controlled anger in his voice as he explains. While German settlers forced indigenous tribes farther into the interior of South West Africa, German researchers treated Africans as mere test subjects. Papers published in German medical journals used skull measurements to justify calling Africans Untermenschen—subhumans. “Skeletons were brought here,” says Kaunatjike. “Graves were robbed.”

If these tactics sound chillingly familiar, that's because they were also used in Nazi Germany. The connections don't end there. One scientist who studied race in Namibia was a professor of Josef Mengele—the infamous “Angel of Death” who conducted experiments on Jews in Auschwitz. Heinrich Goering, the father of Hitler's right-hand man, was colonial governor of German South-West Africa.

The relationship between Germany's colonial history and its Nazi history is still a matter of debate. (For example, the historians Isabel Hull and Birthe Kundrus have questioned the term genocide and the links between between Nazism and mass violence in Africa.) But Kaunatjike believes that past is prologue, and that Germany's actions in South-West Africa can't be disentangled from its actions during World War II. “What they did in Namibia, they did with Jews,” says Kaunatjike. “It's the same, parallel history.”

For the tribes in South-West Africa, everything changed in 1904. Germany's colonial regime already had an uneasy relationship with local tribes. Some German arrivals depended on locals who raised cattle and sold them land. They even enacted a rule that protected Herero land holdings. But the ruling was controversial: many German farmers felt that South-West Africa was theirs for the taking.

Disputes with local tribes escalated into violence. In 1903, after a tribal disagreement over the price of a goat, German troops intervened and shot a Nama chief in an ensuing scuffle. In retaliation, Nama tribesmen shot three German soldiers. Meanwhile, armed colonists were demanding that the rule protecting Herero land holdings be overturned, wanting to force Herero into reservations.

Soon after, in early 1904, the Germans opened aggressive negotiations that aimed to drastically shrink Herero territory, but the chiefs wouldn't sign. They refused to be herded into a small patch of unfamiliar territory that was badly suited for grazing. Both sides built up their military forces. According to Olusoga and Erichsen’s book, in January of that year, two settlers claimed to have seen Herero preparing for an attack—and colonial leaders sent a telegram to Berlin announcing an uprising, though no fighting had broken out.

It isn't clear who fired the first shots. But German soldiers and armed settlers were initially outnumbered. The Herero attacked a German settlement, destroying homes and railroad tracks, and eventually killing several farmers.

When Berlin received word of the collapse of talks—and the death of white German subjects—Kaiser Wilhelm II sent not only new orders but a new leader to South-West Africa. Lieutenant General Lothar von Trotha took over as colonial governor, and with his arrival, the rhetoric of forceful negotiations gave way to the rhetoric of racial extermination. Von Trotha issued an infamous order called the Vernichtungsbefehl—an extermination order.

“The Herero are no longer German subjects,” read von Trotha's order. “The Herero people will have to leave the country. If the people refuse I will force them with cannons to do so. Within the German boundaries, every Herero, with or without firearms, with or without cattle, will be shot. I won’t accommodate women and children anymore. I shall drive them back to their people or I shall give the order to shoot at them.”

German soldiers surrounded Herero villages. Thousands of men and women were taken from their homes and shot. Those who escaped fled into the desert—and German forces guarded its borders, trapping survivors in a wasteland without food or water. They poisoned wells to make the inhuman conditions even worse—tactics that were already considered war crimes under the Hague Convention, which were first agreed to in 1899. (German soldiers would use the same strategy a decade later, when they poisoned wells in France during World War I.)

In the course of just a few years, 80 percent of the Herero tribe died, and many survivors were imprisoned in forced labor camps. After a rebellion of Nama fighters, these same tactics were used against Nama men, women, and children. In a colony where indigenous people vastly outnumbered the thousands of German settlers, the numbers are staggering: about 65,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama were murdered.

Images from the period make it difficult not to think of the Holocaust. The survivors’ chests and cheeks are hollowed out from the slow process of starvation. Their ribs and shoulders jut through their skin. These are the faces of people who suffered German rule and barely survived. This is a history that Kaunatjike inherited.

German colonial rule ended a century ago, when Imperial Germany lost World War I. But only after Namibia gained independence from South Africa in 1990 did the German government really begin to acknowledge the systematic atrocity that had happened there. Although historians used the word genocide starting in the 1970s, Germany officially refused to use the term.

Progress has been slow. Exactly a century after the killings began, in 2004, the German development minister declared that her country was guilty of brutality in South West Africa. But according to one of Kaunatjike's fellow activists, Norbert Roeschert, the German government avoided formal responsibility.

In a striking contrast with the German attitude toward the Holocaust, which some schoolteachers start to cover in the 3rd grade, the government used a technicality to avoid formally apologizing for genocide in South-West Africa.

“Their answer was the same over the years, just with little changes,” says Roeschert, who works for the Berlin-based nonprofit AfrikAvenir. “Saying that the Genocide Convention was put in place in 1948, and cannot be applied retroactively.”

For activists and historians, Germany’s evasiveness, that genocide wasn’t yet an international crime in the early 1900s, was maddening. Roeschert believes the government avoided the topic on pragmatic grounds, because historically, declarations of genocide are closely followed by demands for reparations. This has been the case with the Holocaust, the Armenian Genocide, and the Rwandan Genocide.

Kaunatjike is a witness and an heir to Namibia's history, but his country's story been doubly neglected. First, historical accounts of apartheid tend to place overwhelming emphasis on South Africa. Second, historical accounts of genocide focus so intently on the Holocaust that it's easy to forget that colonial history preceded and perhaps foreshadowed the events of World War II.

This might finally be changing, however. Intense focus on the centennial of the Armenian Genocide also drew attention to brutality in European colonies. A decade of activism helped change the conversation in Germany, too. Protesters in Germany had some success pressuring universities to send Herero human remains back to Namibia; one by one, German politicians began talking openly about genocide.

Perhaps the greatest breakthrough came this summer. In July, the president of the German parliament, Norbert Lammert, in an article for the newspaper Die Zeit, described the killing of Herero and Nama as Voelkermord. Literally, this translates to “the murder of a people”—genocide. Lammert called it a “forgotten chapter” in history that Germans have a moral responsibility to remember.

“We waited a long time for this,” says Kaunatjike. “And that from the mouth of the president of the Bundestag. That was sensational for us.”

“And then we thought—now it really begins. It will go further,” Kaunatjike says. The next step is an official apology from Germany—and then a dialogue between Namibia, Germany, and Herero representatives. Germany has so far balked at demands for reparations, but activists will no doubt make the case. They want schoolchildren to know this story, not only in Germany but also in Namibia.

For Kaunatjike, there are personal milestones to match the political ones. 2015 year marks 25 years of Namibian independence. In November, Kaunatjike plans to visit his birthplace. “I want to go to my old village, where I grew up,” he says. He'll visit an older generation of Namibians who remember a time before apartheid. But he also plans to visit his grandfather's grave. He never met any of his German family, and he often wonders what role they played in the oppression of Namibians.

When Kaunatjike's journey started half a century ago, the two lines of his family were kept strictly separate. As time went on, however, his roots grew tangled. Today he has German roots in Namibia and Namibian roots in Germany. He likes it that way.

Kaunatjike sometimes wishes he spent less time on campaigns and interviews, so he'd have more time to spend with his children. But they're also the reason he's still an activist. “My children have to know my story,” he says. He has grandchildren now, too. Their mother tongue is German. And unlike Kaunatjike himself, they know what kind of a man their grandfather is.

BLOG COMMENTS POWERED BY DISQUS

.jpg)