Following the battle of Moutoa Island in May 1864, Hīpango pursued the retreating Pai Mārire (Hauhau). Fighting continued from fortified positions upriver,

near Hiruhārama. A series of redoubts was built along the river and on the town’s north-western boundary. The killing of provincial councillor James Hewett on his farm in February 1865 raised fears of another attack on Whanganui. Hewett’s farm was only a few kilometres from one of the redoubts.

While Hōri Kīngi Te Ānaua was prepared to act as peacemaker, Hoani Hīpango favoured a military solution – an attitude that ultimately cost him his life. In February 1865 Hīpango was wounded in an attack that he and Mete Kīngi led against the main Hauhau pā at Ōhoutahi, below Pipiriki. The pā was captured but Hīpango died two days later. He was buried with full military honours on Korokota (Golgotha) hill, overlooking Pūtiki. The provincial government erected a wooden obelisk on the site as a mark of gratitude.

|

Mete Kīngi Te Rangi Paetahi was one of the first four Māori Members of the House of Representatives elected in 1868. |

Waitōtara in 1865

Governor George Grey was determined to end the Pai Mārire threat in Whanganui and south Taranaki. In January 1865 General Duncan Cameron and 2000 British troops left Whanganui to reclaim the Waitōtara block for the Crown.

Cameron’s experiences in Waikato and Bay of Plenty the previous year made him too cautious for the governor’s liking. Well aware of the risks involved in attacking pā directly, he kept his men in the open country near the coast. Māori allegedly nicknamed him the ‘Lame Seagull’. When Grey questioned his tactics, Cameron questioned the motive for the campaign, which he believed was to acquire land.

Picket at Nukumaru

Cameron had defeated Hauhau forces at Nukumaru in January and Te Ngaio in March by fighting in the open. Grey was more concerned about Weraroa pā, high above the Waitōtara River north-west of Whanganui. Early in Cameron’s campaign this had become the headquarters of a Māori force of up to 2000 men. The general seemed willing to play a waiting game, considering the pā both too strong to attack and of little strategic importance. Cameron’s lack of action at Weraroa led to the complete collapse of his relationship with Grey.

Grey’s principal allies among local Māori, Te Ānaua and Mete Kīngi, suggested that he negotiate the surrender of Weraroa. The governor would have none of it. Mete Kīngi then advised Grey against a frontal assault, arguing that an attack on Arei-ahi village to the rear of Weraroa would cut off its food supply. When Mete Kīngi’s Māori contingent did this, it found that the main pā had been abandoned by its defenders. Grey seized the political opportunity and accompanied a mixed force of Māori, volunteer cavalry and Forest Rangers into the pā on 21 July.

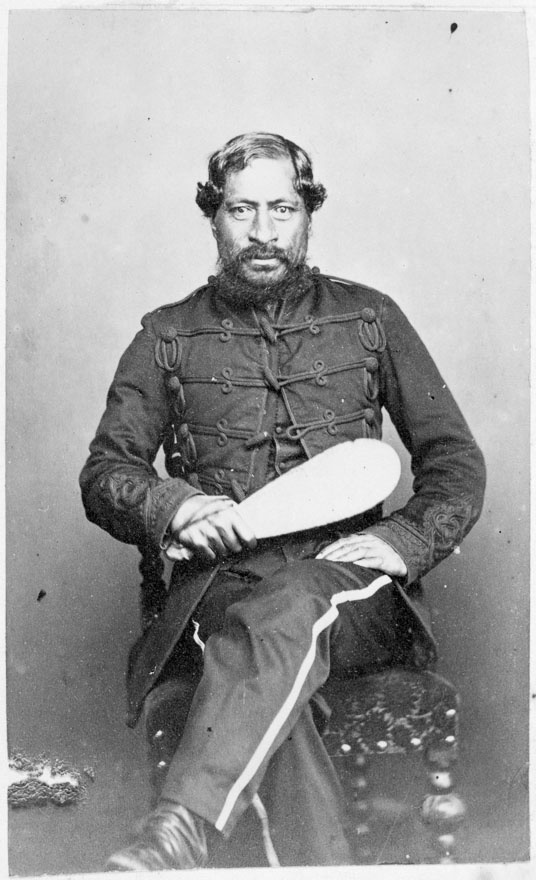

Mete Kingi Te Rangi Paetahi

Mete Kīngi and his men then turned their attention back to the Whanganui River and moved to relieve a force under siege at Pipiriki. Any remaining Hauhau fighters dispersed before it arrived. The abandoned Hauhau village of Ōhinemutu near Pātea was also burned.

With any immediate threat to Whanganui removed, Mete Kīngi proposed to Grey that he and his troops be used to avenge the missionary Carl Völkner, who had been killed by Hauhau at Ōpōtiki in March 1865. Mete Kīngi arrived in Ōpōtiki in September. He was involved in the capture of a number of pā and some 400 Hauhau fighters before returning to Whanganui, where he led the Māori contingent in Major-General Trevor Chute’s south Taranaki expedition of January-February 1866.

The Whanganui-south Taranaki area was now considered to be ‘pacified’. But the confiscation of large quantities of land in the area for European settlement was to lead to the outbreak of Tītokowaru’s war in 1868, when conflict returned to the Whanganui region.

.jpg)

.jpg)