How the remoteness of the Chatham Islands forged a resilient people. Sometime between the years 1000 and 1600, a group of people set sail, likely from the shores of the South Island of New Zealand

, heading east into the great unknown. For days and days, across a journey of 500 miles of stormy ocean, they did not pass a single speck of land. Finally, on the horizon, someone must have seen some distant islands. Today, they are known as the Chatham Islands, and are part of New Zealand. Then, the travelers named them Rēkohu, or “Misty Sun.”

|

|

| New Zealand Maori Regions |

|

These rocky outcrops on the edge of the world would become their home—a faraway and inhospitable land. On this archipelago of two large islands and a freckling of smaller ones, agriculture was near-impossible. It was chilly, rained 200 days of the year, and had relentless winds so powerful that the island’s gnarled trees grew back on themselves, their branches reaching almost to the ground. East of the islands was a near interminable expanse of ocean, with 5,000 miles separating them from the next landmass: South America.

After their arrival, this community of people, who would come to be known as the Moriori, would adapt almost every aspect of their lives to these inhospitable conditions, including their diets, their clothing, their transport, their social structures, and their military practices. For hundreds of years, they lived a pacifist, hunter-gatherer existence—until, in 1835, members of two Māori tribes from mainland New Zealand arrived on the island, killed between a sixth and a fifth of the Moriori, and enslaved the rest.

Exactly how these early settlers came to the Chatham Islands, and what they were looking for, remains a mystery, along with many aspects of how they lived their lives. According to Moriori folklore, quoted by the New Zealand historian James Belich in Making Peoples, “Their atua [god] told them there was land to the east, and they went and peopled it.” The Moriori were descended from the same seafaring people who used double-hulled canoes to discover, and populate, hundreds of islands across thousands of miles of the world’s oceans, from New Zealand to Hawaii to the Easter Islands.

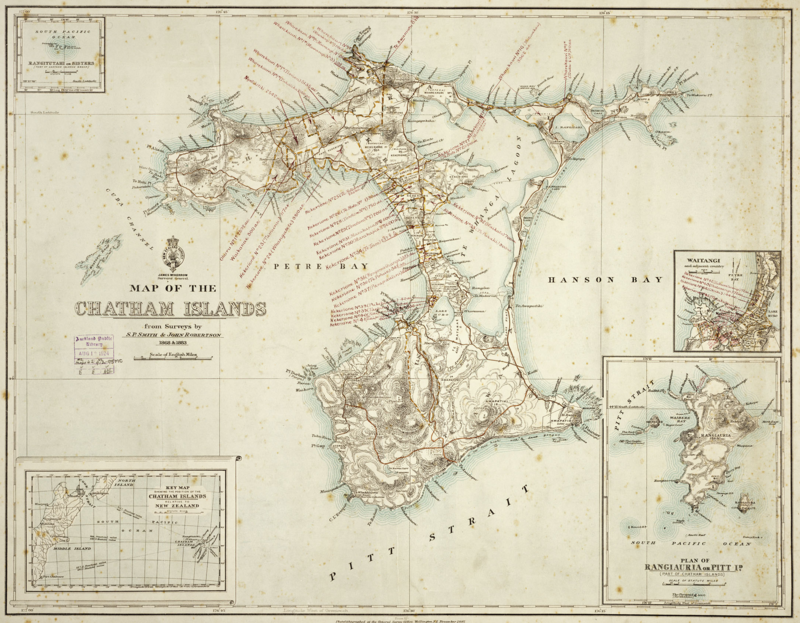

Some of these, like Fiji or Vanuatu, are tropical paradises; others, like New Zealand, are huge land masses—islands so big it would take weeks to walk across them. The Chathams are neither. Chatham Island, the larger of the two main islands, is about 30 miles wide, with about a fifth of its land mass taken up by a central lagoon. Formed by volcanic activity, the islands are fringed by dizzying basalt cliffs, and made up of wildly different topology across a relatively small space. Hill and valleys are thatched with rivers and streams, beneath a green thicket of ferns and nikau palms. Pitt Island, to the south, is around a tenth of the size. The islands, which reach highs of about 65 degrees Fahrenheit in January, are both too cold and too inclement to grow traditional Polynesian vegetables, like sweet potato, taro, or yam. The Chatham Islands have no native land mammals, but a large population of leggy shorebirds and forest fowl, including warbling tui and the melodious bellbird.

To survive, Moriori had to look to the sea. Within a couple of centuries of their arrival, they had developed a functional way of life that remained largely unchanged until the arrival of Europeans in 1791. Instead of developing traditional agriculture, they learned to manipulate the islands’ wild plants, the late historian Michael King wrote in the 1989 book Moriori: A People Rediscovered, “especially kopi—for its berry kernels—and fern root, which they grew in clearings and around the edge of the kopi groves, where the richer soil gave it a pleasantly nutty taste.” Of the hundreds of types of plants on the Chatham Islands, perhaps 30 were edible, King wrote—and none of them especially tasty.

Most of day-to-day existence on the Chathams, therefore, was spent gathering food from the sea that the Moriori needed to survive. In the calmest months of the year, from October through to April, King describes how women and children were tasked with assiduously pulling certain types of shellfish from the rock. Around the same time of year, when the sea was at its least perilous, men used nets woven out of flax to catch cod, grouper, moki, and tarakihi. Year-round, the Moriori hunted seals, which provided them with blubber, meat, and skins, which they used to make waterproof cloaks, with the fur facing inwards. Crayfish, seaweed, and a few coastal and forest fowl rounded off this largely seaborne diet.

There was enough to eat on these remote islands, but life was hard—and often short. Average life expectancy, according to King, maxed out at about 32, with around a third of the population dying in infancy. What killed them was not predators, warfare, or starvation, but damage to their teeth from a lifetime of gritty shellfish. This, in turn, often led to bacterial infections, which were worsened by the respiratory problems common to a damp, cool climate.

The Moriori had come to the islands on double-hulled canoes, but the harsh environs demanded their transformation, too. These were adapted into vessels better suited for fishing in the rough seas around the archipelago. Called korari, or wash-through rafts, they had a floor and sides made of bound reeds, and used inflated kelp to remain afloat amid harsh winds and choppy seas. Some were as much as 50 feet in length, and used to go out to offshore rocks to kill seals or albatross.

But the greatest shifts in lifestyle weren’t in diet or transportation. Being so remote, with a population of just 2,000 people, required an overhaul in the political structure of society, and how disputes were resolved. Moriori coexisted in tribal settlements of up to 100 people, scattered across the two bigger islands. In 1873, the magazine Catholic World published an extended interview with Koche, a Moriori man who had found work with an American vessel. They had lived “in peace and plenty for centuries,” he said, “enjoyed a democracy and conducted their simple affairs by a council of notable men.” In similar Polynesian societies, however, bloody tribal warfare was common—in mainland New Zealand, cannibalism remained a feature of many clashes between Māori iwi, or tribes. But the Moriori adopted pacifism, known as Nunuku’s law.

Alexander Shand, in an early journal article on the Moriori, describes how Moriori ancestor Nunuku-whenua had “proclaimed a law which was honoured and kept until the Māori invasion… ‘Ko ro patu tangata, me tapu to-ake’ (Manslaying must cease henceforth forever).” According to Moriori custom, if physical conflict were truly necessary, men could hit at one another with tupurau, poles the width of a man’s thumb and a couple of feet in length. But the moment blood was shed or skin broken, they were obliged to stop. Nunuku offered a warning for those who disobeyed his law, King writes: “May your bowels rot the day you disobey!”

Elsewhere in the Pacific islands, men proved their strength and masculinity through warfare and enduring the pain of tattoos across their entire bodies. Moriori seem to have abandoned tattooing, however, and instead, King writes, substituted other activities as ways to prove their worth. “One was the demonstration of bravery on birding expeditions, particularly when landing on sheer or even concave rock faces; another was the manufacture of a hafted adze [a type of ax]; and a third was the capacity to dive in rough seas for crayfish and come up with one in each hand and a third in the mouth.” These factors influenced who was made ieriki, or chief, rather than the standard heredity on other Polynesian islands.

Shand lived among Moriori on the Chathams in the late 19th century for some years, and described their lifestyle in detail in the Journal of the Pacific Society. Rather than fighting, he wrote, Moriori tribes would “organize expeditions” to one another’s patches and, on arrival, “recite incantations for the success of their party, just as if in actual warfare.” (These “incantations” may have resembled the Māori haka, made famous internationally by the All Blacks.) Generally, however, they lived peaceably—marrying as teenagers, having large families, and living in unfortified, A-shaped houses, lined with bark for warmth. In times of plenty, they ate three meals a day; when supplies were scarce, only one.

Through an intricate system of rules and rituals, Moriori developed a way of life that ensured their long term survival while preserving the natural world. Hunting expeditions were cooperative, rather than competitive, and particular species of animal banned from consumption during some months of the year, to give them time and space to stabilize their populations. Nunuku’s law may also have been a way of protecting themselves from one another—with such a small population, they simply couldn’t afford to lose members of society over quibbles that became violent.

Perhaps Moriori would have continued these peaceful mores into the present day. In November 1791, however, a navigational mishap sent a British Navy ship, HMS Chatham, careening further south than intended—and into the path of the Chatham Islands, which would soon be named after the vessel. When they saw the ship, Moriori came down to the shore to greet these new arrivals. According to the ship’s log, “as soon as they saw us land now advanced hastily, and by their threats and gestures plainly indicated their Hostile intentions.” The British had encountered indigenous people before, and did not seek a fight—the Moriori, on the other hand, had been separated from other people for centuries, lacking either a word for people who were not like themselves, or a word for their own culture.

Returning to the ship, the British decided to “engage their friendship,” returning with an offer of helmets, beads, and red cloth. They hoped to be given food and water; Moriori did not oblige. Amid a to-and-fro of miscommunication, a skirmish ensued, and a Moriori man, Tamakaroro, was shot, and his body left on the beach.

When the British left, the Moriori decided that they were the guilty party in this fight, and had dishonored Nunuku’s law. Tamakaroro’s body was left on the shore, and the British were gone—the “Sun People,” perhaps named for the paleness of their skin, were not in fact the cannibals Moriori believed them to be. On their return, they decided, they would be greeted with a sign of peace.

Within 50 years, foreign ships had become a common sight on the Chathams. Though few official records were kept, British and Australian ships alike flocked to the islands to slaughter animals by the thousands. Moriori had killed only male seals, and mostly the older ones, but European sealers were indiscriminate, leaving the animals they had skinned to rot on the islands. These fetid carcasses drove away the rest of the seals: By the 1830s, King writes, almost all of them had gone from the island, depriving the Moriori of a key food, fuel, and winter clothing source.

Despite these affronts, the Moriori maintained their pacifism. By 1835, a relatively peaceful and content community of around 1,600 Moriori lived alongside newcomers from mainland New Zealand and Europe. Aspects of Moriori life had been altered irremediably, with pigs replacing seals and introduced cats and dogs decimating populations of native birds, but things were not so different to how they had always been. They had continued to obey Nunuku’s law, even in the face of pathogen- and weapon-bearing visitors, and had been mostly left alone. The religious practices, language, and family structures developed over centuries seemed safe.

But in 1835, members of the Māori tribes Ngāti Tama and Ngāti Mutunga, living in what is now Wellington, New Zealand, decided to migrate to the Chatham Islands. Around 500 men, women, and children arrived on the shore, determined to take the land they found there through a practice called “walking the land,” where they moved across the island and settled wherever they liked. Moriori who disagreed or attempted to retain their districts were summarily slaughtered.

King describes how about 1,000 Moriori gathered to discuss what they should do. This invasion was different to previous arrivals, who had come, taken resources, and then left again. Some younger men argued that Nunuku’s law was designed to protect them from one another, and did not apply to those who were not Moriori. They needed to fight back, they said, or risk certain death. Older chiefs disagreed. Nunuku’s law was a moral imperative. Disobeying it would compromise their mana, a complicated and multifaceted term comprising integrity, prestige, and strength. The Moriori resolved not to fight. The Māori, King writes, seem to have decided at roughly the same time that a pre-emptive strike was necessary.

Shortly afterwards, hundreds of Moriori were slain by Māori. They did not fight back. “They commenced to kill us like sheep,” one survivor said later, “wherever we were found.” At least 220 men and women were killed, and many more children.

Recordings of a council of Moriori elders from 1862 lists all adult Moriori alive on that day in 1835. One cross meant they had died or been killed; two crosses meant they had been cooked and eaten, a Māori custom common to land disputes on the mainland. Those who had not been killed were enslaved, separated from their families, and prohibited from marrying. Many died of illness, overwork, or kongenge, meaning dispiritedness or despair. The historian André Brett argues that what took place was not mass killing, but systematic genocide: “Māori viewed Moriori as a different and inferior people and killed individuals on the basis of their membership of the Moriori group.” In fact, they were genetically indistinct from one another.

Within 30 years, there were only around 100 Moriori people left. An already broken people suffered injustice after injustice—30 years of slavery; the awarding of 97.3 percent of the Chatham Islands to Ngāti Mutunga Māori in an 1870 Native Land Court decision; and the systematic portrayal of Moriori as a “lazy, stupid people,” genetically distinct from Māori and Polynesians, in a 1916 copy of School Journals, a series of educational magazines used across New Zealand elementary schools. In 1933, the last “full-blooded” Moriori, known as Tommy Solomon, died, causing many to claim that the Moriori were gone for good. Despite it all, a few hundred Moriori descendants continued to eke out an existence for themselves in New Zealand, albeit far from the Chatham Islands, in a country that often failed to acknowledge their presence or what had happened to them.

Since the 1980s, however, these historical atrocities are beginning to be recognized for what they were, mostly due to the continued efforts of the 900 or so Moriori still living in New Zealand. In 1994, a New Zealand tribal tribunal awarded Moriori a share of the Chatham Islands’ rich fishing resources; in 1997, construction began on the first Moriori marae, or meeting house, on the Chatham Islands in over 160 years. This was completed in 2005.

In 2011, New Zealand’s Education Minister, Anne Tolley, travelled to the islands to present Moriori with a new series of School Journals that told their story accurately. The article, headlined Moriori: A Story of Survival, dispels a century of accrued slander about the Moriori—another step in the reparations process for a people who, from their first arrival on the Chathams, have survived and thrived no matter the odds.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)